Adeline André: “There is only the fabric and the body in motion. It is a symbiosis.”

Adeline André’s style has withstood the constant shifts of fleeting trends since the launch of her House in 1981. Dubbed “Mother of Minimalism” by The New York Times in 1993, the designer remains driven by a humble and unwavering pursuit of precision in cut and drape. She now presents her Haute Couture Fall-Winter 2025/2026 collection - an opportunity to reflect on a singular journey, guided by an innate passion for movement and purity.

Adeline André explores elegance in simplicity, through a pared-down aesthetic that requires far more rigour than any form of excess. This exacting approach is rooted in a journey marked by insatiable curiosity and an open outlook on the world. Born in Bangui in Equatorial Africa, André grew up in Paris before flying off to London to pursue her dream of becoming a fashion photographer. “The mid-sixties in London were such a fun, exhilarating time. Fashion, music, there was incredible effervescence,” she recalls. Upon returning to Paris, she enrolled at the École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, "a very classical school," and was admitted directly into the second year "because I was already making clothes myself.” At the same time, she attended drawing classes given by Salvador Dalí at the Meurice. “I completely understood that in every garment I could draw, there would be a three-dimensional body that moves. That anchored in me.” Her career began in grand style when she joined Christian Dior in 1970 as assistant to Marc Bohan, artistic director from 1961 to 1989. The latter revolutionised the House by creating the ready-to-wear line Miss Dior, children's Baby Dior, and men's Dior Monsieur. I must say that haute couture was very old-fashioned at the time and ready-to-wear was very promising. But I didn't see things that way. I was happy to be working and discovering this universe.”

There, she discovered the hierarchy of the Haute Couture workshops and attended all the fittings. “There were still eight Haute Couture workshops, from the most tailleurs to the most flou, and the people resembled their work. At the Coat workshop, there was a tall man, very square-built. At the flou workshop, a man was completely hunched over. That really struck me.” She encountered the marvels of technique, so meticulous that it disappeared, as with this chiffon dress that she glimpsed during a fitting. “The dress passed in front of me and it was smoke. I saw smoke. It’s an effect you can easily achieve in photography, but in couture... They explained to me that they had used seven layers of fabric, from midnight blue to flesh tone.” She then explored the style offices, the trend books, and even assisted Jean-Charles de Castelbajac. “We'd met by chance, at Les Halles. Fashion was a very small world, everyone crossed paths. It was quite a fantastic period. Sometimes, in ELLE magazine, I'd read the name of someone whose work I admired and I'd telephone them.”

“It was natural for me to know what type of clothes I wanted to make, what I deeply wanted to show and bring to fashion, without being pretentious. I wanted to contribute something.”

In 1981, alongside István Dohar who still accompanies and supports her, they set up the Adeline André company. Right from the start, she designed a piece that remains one of her great signatures, the three-armhole garment. “It came to me as I was falling asleep, the idea of wrapping oneself up.” Resolutely focused on ready-to-wear at the beginning, she designed clothes that could be made quickly. “It's really a question of cut, with very simple assembly. You wrap yourself in it, it's ergonomic. There are no accessories, buttons, or fastenings. And I've always wanted to work with natural fabrics with beautiful quality.” Some models of three-armhole garments are notably presented in museum collections including the Palais Galliera in Paris, the Fashion Institute of Technology Museum in New York, and the Design and Fashion Museum (MUDE) in Lisbon.

From her very first collections, her style was clearly defined. At the height of padding and stretch, André offered her elongated silhouettes with soft shoulders, in natural and flowing materials. “There's never any interfacing, never shoulder pads, padding, or boning. As few seams as possible, no conventional lining because the garment must be as beautiful inside as out. I've always followed that principle. There's just the fabric and the body. It's a symbiosis.” She designs her creations for bodies in movement, like the turning trouser-dress: “From the side, it looks like trousers, but when you walk, it turns. Movement creates the garment.” She clung to ready-to-wear but found herself drawn into Couture, into bespoke work, almost despite herself. “We kept trying to do ready-to-wear, but we didn’t have the financial and commercial structure. We could never cope with the boutique orders.” In the years that followed, she devoted herself exclusively to her private clients. She met Simone Bodin, a model known by the nickname “Bettina” given to her by couturier Jacques Fath. “Bettina ordered lots of clothes from me and brought me clients. I started doing bespoke work quite naturally.” She created new made-to-measure pieces that she unveiled at her 'Topofwear gatherings'. “István came up with that name as a play on Tupperware parties,” she smiles - in galleries, workshops or friends' salons in Paris, London and New York. In 1993, American journalist Amy Spindler dubbed André “Mother of Minimalism” in The New York Times, recognising even then her consistency and ability to enhance the essential. "I was pleased because at the time, that term was only used in art, not for fashion." When she was fully absorbed by crafting bespoke pieces, she joined the Official Calendar of Haute Couture Week in 1997. She gained the protected “Haute Couture” designation in 2005. “Suddenly lots of journalists were calling me. Fame didn't interest me. I wanted to work and earn my living - it's not more complicated than that.”

“My clients are architects, artists, people who work. I make simple things. I love drawing and sometimes I get experimental. And then I come back to my line.”

For her Haute Couture Fall-Winter 2025/26 collection, André showcases her signature style, with a very special piece. “I'm showing something special, what I call the Poiret coat.” It all started with a 2005 Drouot auction featuring pieces from Denise Poiret’s wardrobe. Denise was the wife and muse of the legendary couturier who freed women from their corsets a century ago. One lot caught everyone's attention: a 1914 motoring coat in thick linen and ivory silk described by the auction house as woven “in a jute style with indigo blue chevron stripes across the bust.” When the hammer fell at €131,648, it set a world record for early 20th-century couture. “I couldn't get that coat out of my mind. Poiret used to travel to Morocco and had bought this rough, undyed peasant blanket. He transformed it into a coat with a kimono collar and these sleeves that swept upwards.” Her first homage came in turmeric yellow, but she had no idea where it would lead. “Last year, Marie-Sophie Carron de la Carrière from the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris visited my workshop. When I told her the story, the museum actually bought my coat for their collection.” One can see it in the “Paul Poiret: Fashion is a Celebration,” exhibition running until January 11, 2026. A chance to explore the work of the man who revolutionised haute couture, alongside André's contemporary tribute. “For this new collection, I've remade the Poiret coat in midnight blue cashmere. I do extensive fabric research and have many specially dyed. In Japan, they've preserved old small factories. You can find, for example, silk chirimen - pure silk, very crêped, that doesn't wrinkle at all," she explains, delicately stretching a sample. Her fabrics also come from Italy, where she finds "ranges of georgette in countless colours. And other materials that can't be dyed. Organza, for instance - if you wet it, it becomes like chiffon. Impossible to dye. Leather satin too - it's too thick.” Each material has its origin, its personality, its reactions.

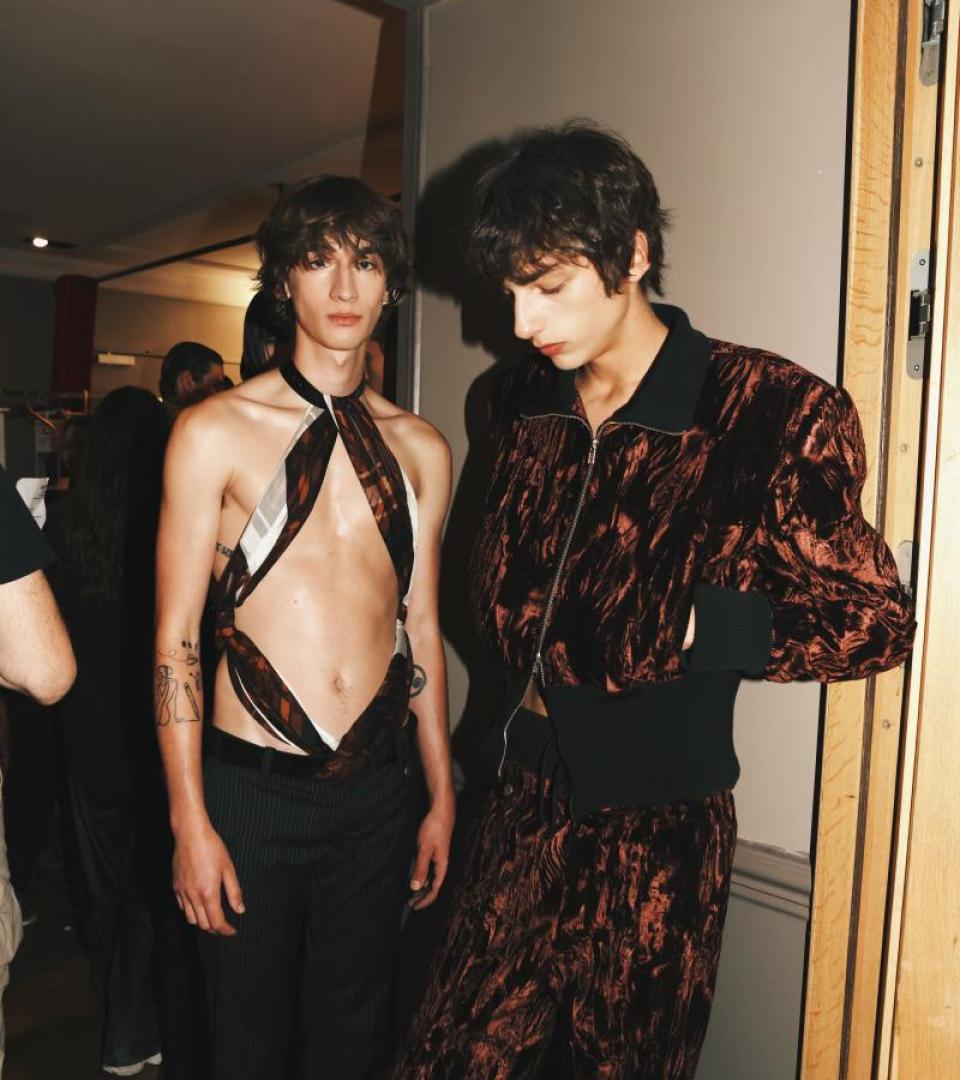

André creates and shows her collection at La Ruche, where her workshop is located. This famous Parisian artists’ beehive has welcomed talents like Chagall, Modigliani and Léger. Founded in 1902 by sculptor Alfred Boucher, La Ruche gets its name from the ‘bees’ metaphor Boucher used for his young protégé artists. “There's an exhibition space that artists can book. Like my previous show, I've decided to display some older pieces.” The exhibition runs until July 14.”

“Dance is amplified movement and I dreamed of designing costumes.”

Alongside her Haute Couture collections, she creates costumes for theatre and opera. In 2017, she designed costumes for the performance “Set and reset/reset” by American choreographer Trisha Brown at Lyon Opera. In 2022, she worked with choreographer and scenographer Angelin Preljocaj. “He sent me the synopsis and I did drawing after drawing. Which was fine because I love drawing. He kept changing his mind and at the dress rehearsal, he'd cut all the turning trouser-dresses. I told him the ballet was beautiful but I was sad he'd removed the dresses. He said he was putting them back because he was thinking of me and wanted to please me.” The photograph became the ballet poster and the dresses received many compliments. “For dance, for ballet, it's wonderful seeing these dresses on stage because of the lights, the movement.”

In 2011, thanks to “Lefèvre, she met Alexei Ratmansky, based in New York, who asked her to design costumes for “Psyché” at the Paris Opera. “I enjoy working with him because it's easy, he's profoundly kind. He has wonderful taste in colours and a brilliant eye." She then designed costumes for “Symphonic Dances,” then for the ballet "Pictures at an Exhibition" to Mussorgsky's music, which premiered in New York then travelled to Munich, Vienna, Seattle, Miami... and is heading to London. “Alexei asked me to draw inspiration from Wassily Kandinsky for the costumes. It was great fun. István chose small motifs that I placed on the costumes. The motifs moved with the dancers.”

Haute Couture, costumes and even ceramics: André loves creating beautiful, lasting objects. In 2013, she met René-Jacques Mayer, then Director of Creation and Production at the Cité de la céramique - Sèvres and Limoges, now general director. “I told him I'd love to do something. I thought of a dinner service, because I felt that nowadays many people are changing how they eat, how they sit at table. I felt we were moving away towards different shapes, which I exaggerated.” The result was a set of bowls in varying, harmonious sizes and colours, arranged around a central plate. “First geometric, then a bit wild, aquatic. István found the name for this service: Archipel.” André continues the same quest: creating pieces to keep for life, where movement and material are in constant dialogue.

Reuben Attia