Essence is…

Ekow Eshun is a writer, journalist, broadcaster and curator. He is the editor-in-chief of the quarterly magazine Tank and the former director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts. He is Chair of the Fourth Plinth Commissioning Group and Creative Director of Calvert 22 Foundation. Ekow Eshun shares his notes on Wales Bonner’s lyrical film “Thinkin’ Home” directed by Jeano Edwards and shot in Jamaica. The film is a view on Wales Bonner’s ESSENCE womenswear and menswear Spring-Summer 2021 collection.

Essence is ‘the intrinsic nature or indispensable quality of something, especially something abstract, which determines its character.’

Essence is a collection.

Thinkin’ Home, the elegant, lyrical film made in collaboration between the filmmaker Jeano Edwards and Grace Wales Bonner is shot in Jamaica. It tracks the passage of eight young men as they journey across the island, the landscape pulsing with the sound of ‘80s dancehall and spoken word, the chatter of bird call and the crash of waves against the shore. Throughout, there are moments of startling beauty. A magisterial waterfall. A row of storefronts painted in soft hues of blue and yellow and pink. The island, seen from out at sea, sitting low on the horizon between the ocean and a twilit sky.

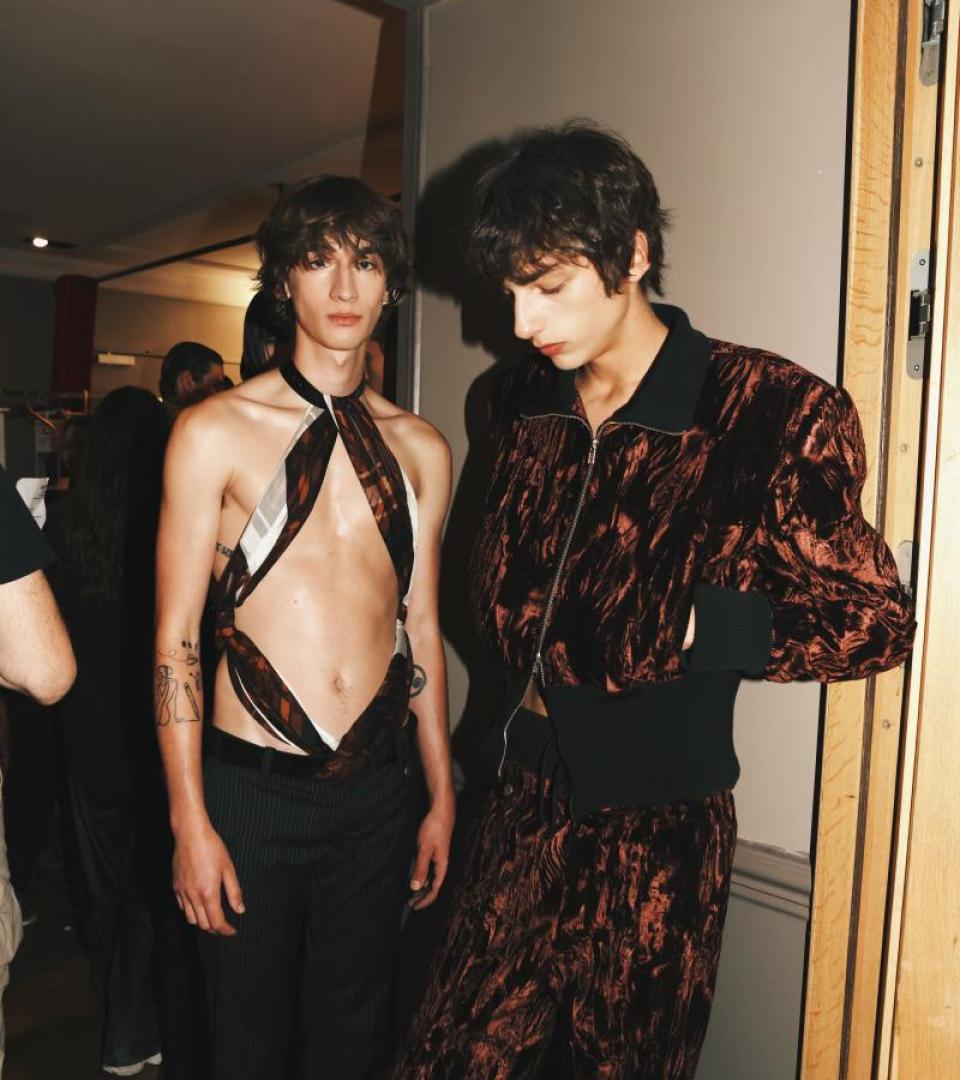

Thinkin’ Home is made in complement to Essence, the Spring Summer 2021 Wales Bonner collection. The designer describes how her goal with the collection was to ‘refine my craft’ and ‘make something very meaningful and pure. It was an exercise in defining what the codes of the Wales Bonner house are.’ A similar pursuit of spirit and sensibility informs the film. Edwards was born in Jamaica and he conjures the island flickering and evanescent, a place that is ‘ever changing,’ inhabited by a people of ineffable stylishness.

Thinkin’ Home draws inspiration from the ‘70s Jamaica of the movie Rockers, the dub poetry of Mikey Smith, Bob Marley at home at 56 Hope Road. The aim perhaps being not simply to look back at a time gone by, but to explore how a generation of black men in a given era moved through the world; how the essence of a place and people is revealed through the grammar of their gesture, language and dress.

Essence is liberation.

The Legend of the Flying Africans is founded in an act of collective resistance. In May 1803 a group of captive Africans stage a revolt on a slave ship as it nears America. The ship is bound for St Simons Island, off the coast of Georgia. As it approaches its destination, the captives, who belong to the Igbo people of West Africa, rise up against the crew, force them to jump overboard and then run the vessel aground. Once on land, the Igbos are said by an eyewitness to have ‘taken to the swamp’. Rather than risk being returned to captivity they line up hand in hand, walk into the water and drown together, committing mass suicide. Other accounts tell a different story. Instead of submerging themselves, it is said the Igbos raised up their arms, invoked their gods and took to the sky, soaring back home over the ocean. In the wake of that original 1803 revolt, the tale of the Flying Africans has been told for generations across the Atlantic world. For the most part, the story of their escape is recounted as folklore, a poetic evocation of a desire to fly from a state of oppression. But we might reasonably also look at the tale as something more than just metaphor. One way for enslaved African peoples to resist assimilation into the New World was to hold on to the religious and spiritual practices of their homelands. This in opposition to Western tenets of progress, equality and knowledge which provided the ideological cover for the injustices of the slave trade. As the scholar Jason R Young has noted, retaining a connection to the spirit realm ‘also afforded to enslaved men and women new avenues of bodily movement – in spirit possession, transmigration, dance and flight – that rejected the idea of their bodies as merely an extension of the masters’ will, as merely a discrete tool meant to produce and reproduce’. Even if it’s not literally true, the Legend of the Flying Africans is perhaps more than just superstition or any of the other names used to discount beliefs that fall outside Western epistemologies. Its power, its persistence, is maybe because of the dazzling act of inversion that lies at the heart of the story. The shackled take flight. Africans see further and reach higher than their white subjugators. A dream has the moral clarity to outshine waking life.

Essence is enemy.

To be black means to always be subject to the white gaze. In The Souls of Black Folk, WEB DuBois, the great seer of race, coined the term ‘double consciousness’ to describe the ‘peculiar sensation’ of living as a black person physically within, and psychologically outside white society: ‘this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity’.

Being prey to the white gaze means functioning as an object of prejudice and fascination and psychological projection. The tropes are familiar ones: black women as angry or lascivious. Black men as creatures of overdeveloped musculature and ungovernable sexuality, liable to lapse into violence and lawlessness. By this formulation, our character is defined by our colour. Our race is our essence.

This is a subject that Frantz Fanon turns to in a pivotal scene in Black Skin, White Masks, when he describes a white boy’s startled reaction at Fanon’s approaching figure. Clinging to his mother, the boy cries, ‘Look, a Negro!…Mama, see the Negro! I’m frightened.’ For Fanon the moment is one of psychic assault. He is forced to see himself through the eyes of the child, as brute and threatening, and then dumped back in his own skin, objectified and humiliated. ‘My body,’ he writes, ‘was given back to me sprawled out, distorted, recoloured, clad in mourning on that white winter day.’

This sensation of bodily remove is also at the heart of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. The novel’s hero discovers that his blackness renders him beneath sight to most white people, even as it lends him a heightened visibility across society, as a stereotypical object of fear and fascination. He is denied voice or agency or subjective existence. ‘You ache with the need to convince yourself that you do exist in the real world,’ writes Ellison, ‘That you’re a part of all the sound and anguish…you curse and you swear to make them recognize you. And alas, it’s seldom successful.’

Essence is the discrepant spirit of a young republic.

Consider these men. Each of them dressed like royalty. Which is to say with the freedom and self-assertion of those who acknowledge no rulers. There are four of them. Kings without a country. One wears a vivid yellow tracksuit unzipped to the navel. Another is in brilliant green trousers and a striped cardigan. A third is dressed in a shirt and trousers composed of contrasting shades of pink. The last of them wears a waistcoat and flared jeans in multicoloured patchwork denim.

We glimpse these men, in passing, in the glorious reggae movie, Rockers. Truth to tell, in other circumstances they’d likely be overlooked as strivers on the edge of the social system in Jamaica. But in the splendour of their self-regard, we see how stylishness makes them visible on their own terms here on the streets of Kingston.

Their assurance brings to mind Tina Campt’s notion of the practice of refusal: ‘a refusal to recognise a system that renders you fundamentally illegible and unintelligible; the decision to reject the terms of diminished subjecthood with which one is presented. Using negation as a generative and creative source of disorderly power to embrace the possibility of living otherwise.’

Essence is the unfamiliar.

‘The land, the people, the light’, goes the motto of St Lucia and across the West Indies, the richness and wonder of the Caribbean landscape has invited comparisons in the Western imagination with an Edenic paradise. In his 1992 Nobel lecture, Derek Walcott reflected on how a nature ‘so exultant, so resolutely ecstatic’ was miscast as pure and benign and Arcadian. The West, he bemoaned, had ‘looked at a landscape furious with vegetation in the wrong light and with the wrong eye.’ Look more attentively and you see that the palm trees and ferns and fauna of the Caribbean have been shaped by a past of conquest and colonialism. History, says Walcott, is inscribed ‘in Antillean geography, in the vegetation itself.’ When Europeans arrived on the islands they brought with them ‘portmanteau biota’ – plants, animals, microbes, diseases – that radically remade the ecology of the West indies over short centuries. To look at the landscape now is to see the evidence of a legacy of violence. But it’s also to bear witness to a dance, a dialogue, a patois. Sugarcane, yam, coffee, banana, breadfruit, mango, coconut, ackee are not historically native to the Caribbean but they are now emblematic of the Caribbean. Nature speaks a creole of human agency and exchange. But the effect of such accelerated change, of a geography so intertwined with the power relations of its inhabitants, is unsettling. What is native or foreign, new or old, indigenous or alien? Even for those born on the islands the terrain can feel unfamiliar. Belonging is elusive, reflects Walcott on growing up in the Caribbean. ‘We were all strangers here.’