Vivienne Westwood, Disrupter and Dame

The disruptive British designer Vivienne Westwood passed away on December 29th at the age of 81. Despite the awards and honours, Westwood, who was appointed Dame Commander of the British Empire in 2006, remained a rebel at heart with her dishevelled red hair and trademark look. “The only reason I’m in fashion is to destroy the word conformity”, she stated unapologetically.

Yet nothing predestined a mere schoolteacher to grow into a style icon. Her first meeting with Malcolm McLaren in 1965 marked a pivotal moment in her life. He became her mentor. He challenged the young woman to shape the dress codes of young people who aimed to disrupt every norm. Together, they opened a boutique at 430 King’s Road in 1971, which turned out to be a punk landmark by combining fashion and music. It was a sharp turn from the angelic idealism of the hippies. “We weren’t only rejecting the values of the older generation, we were rejecting their taboos as well,” she observed, reflecting on the period.

Credits : Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert / Alamy Stock Photo

Over the years, the boutique switched names from Parade Garage to Let It Rock, Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die, Sex, Seditionaries and finally, World’s End. The suits and denims of the Teddy Boys movement were replaced by the more daring biker looks, followed by fetish outfits. The legendary Sex Pistols, managed by Malcolm McLaren, figured among the ambassadors of this new style. From 1975 onwards, this band and the designer were instrumental in defining essence of what would become punk grammar: slashed trousers and T-shirts, torn jackets, provocative messages such as “anarchy” or “destroy”, razor blades, safety pins and more. They completed this revolutionary and irreverent silhouette by tearing up highly respectable Royal Stewart Tartan of Queen Elizabeth II was appropriated, torn up – an iconoclastic statement against the conservative mood of the moment.

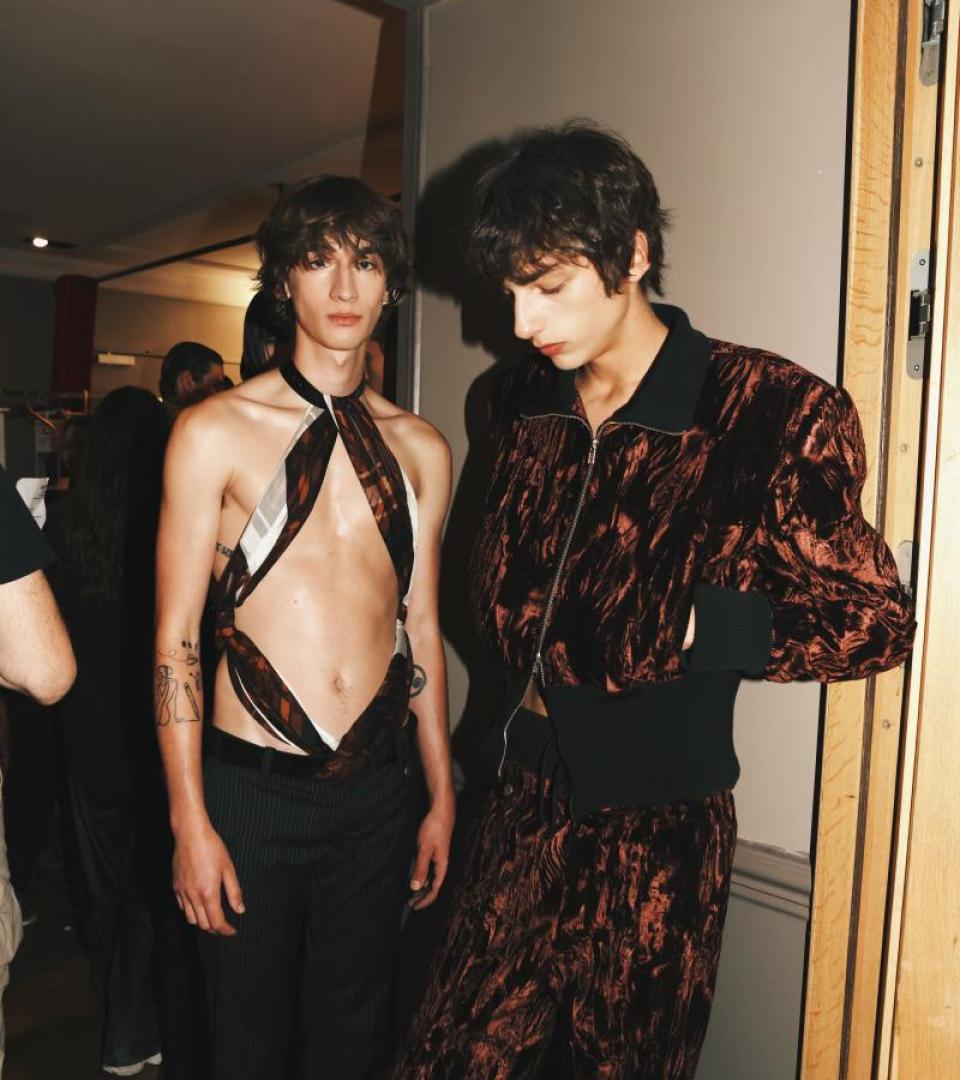

A decade later, she freed herself from punk. Her first collection “Pirate”, in 1981, was the beginning of her search for beauty in subversion. “The only thing I believe in is culture”, she maintained. Her pirates conjured up history, mythical figures from the Western psyche. But they also represented libertarians who fight against the established order. The designer increasingly drew inspiration from old costumes, particularly from the 18th century, without losing the radical nature of her message. The paintings of Antoine Watteau or François Boucher and the watercolours of Pierre-Joseph Redouté provided patterns evoking gallantry and a libertine spirit. The historical references, albeit never literal, inspired the designer who was passionate about technique. Corsets, French dresses, necklines and court dresses were distorted, inflated and reconstructed. “Coquetry is part of feminine wisdom,” Westwood once remarked. By no means superficial, there is a hedonistic celebration in the designer’s work. Freedom translates, among other concepts, into unbridled enjoyment of life’s pleasures.

In 1992, she married Andreas Kronthaler, who was 25 years younger. The designer, whom she had met at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, joined her studio in 1989. From then on, he became her creative right-hand. Since 2016, his Gold Label line bears the name Andreas Kronthaler for Vivienne Westwood to acknowledge this essential role. With such a singular approach, season after season, Vivienne Westwood’s collections have consistently asserted their fashion without being fashionable. “My clothes have a story. They have an identity. They have a character and a purpose. That’s why they become classics. Because they keep on telling a story. They are still telling it”, she has said. Heritage and history constantly serve as a source of inspiration for the designer.

Fashion was just a pretext for Westwood to shake up a society locked in the artificial happiness of consumerism. And one of her weapons is culture. Throughout her four-decade career, she has built bridges between the past and the future. “The best fashion accessory is a book,” she conceded ironically. The provocation was not confined to offending Puritan minds. It was a clarion call for awareness. She was a pioneer and one of the most zealous activists in favour of responsible and sustainable fashion. In 2007, she published her manifesto, Active Resistance to Propaganda, a war declaration on over-consumption. This widely relayed pamphlet was one of the first to advocate for real action in the fashion industry. In 2016, she published Get A Life, an activist essay that takes the form of a diary that is part of her awareness-raising process.

While she was inherently rebellious, her creative impulse was not nihilistic. Indeed, this is what sets her apart from her beginnings and the punk movement. One of her oft-quoted comments reveals her sense of free expression: “I use fashion just as an excuse to talk about politics. Because I’m a fashion designer, it gives me a voice, which is really good”. It was her yearning to build a better world out of the ruins of an imperfect present. And it is owing to incomparable individuals like Vivienne Westwood that fashion may claim its raison d’être.